A Cambrian explosion of Hamurabi clones diverged throughout the 70's, undoubtedly driven by David Ahl's BASIC conversion. The emphasis on formulas appealed to the computer nerds of the day, its primitive implementation lent itself well to expansion, the BASIC language made this simple, and programmers around the world took their shots at it, sometimes in subtle ways, sometimes producing entirely new games. Like so many Cambrian species, the vast majority are extinct, forgotten, with not even a fossil record to remember them by, and yet, virtually all economic simulation games owe their lineage to this event.

One of the most successful of these games was Santa Paravia and Fiumaccio, a city management title originally published in the December 1978 issue of SoftSide Magazine as a TRS-80 BASIC type-in program, where it's billed as Santa Paravia en Fiumaccio

and credited to Rev. George Blank. It was successful enough to receive

an expanded tournament edition, ports to Apple II and Commodore

computers, and a graphical remake on 16-bit machines in the late 80's.

The full extent of its influence is unknown, but designer Brian Reynolds

cites it as an influence.

In Santa Paravia, you own a sizeable fiefdom in 15th century Italy and are tasked to develop and expand it into a city-state, with the ultimate goal of recognition as a king or queen - a title contingent on accomplishing tasks such as accumulating money, land, population, and city improvements.

Up to six players may compete with the goal of being first to reach the highest rank, but interaction is limited. Each player gets their own fiefdom, with player one owning Santa Paravia, player two owning Fiumaccio, player three owning Torricella, and so on. Apart from the race to the crown, the only means of interaction is the possibility to steal another player's lands, should your army become much larger than theirs.

There are quite a few versions of Santa Paravia available to download, most of them as loose BAS files, but I'm not sure I trust these to be accurate to the type-in. Quite a few have typos, and a number all have a coding error where a 50% interest rate is incorrectly calculated by adding 1.5 to the debt instead of multiplying by it. I've instead chosen to play the cassette version distributed by Instant Software Inc around 1979-1980, knowing that it features some minor enhancements over Blank's original.

I spent some time puzzling over Santa Paravia's mechanics - the instructions don't really tell you how to succeed, or even what your goals are. The article in SoftSide goes into some detail, but a lot of the information there is wrong.

The first thing you might want to understand about Santa Paravia is how to achieve ranks. There are twelve goals, mentioned in the magazine but not the ingame instructions:

- Build 10 markets

- Build 10 palaces

- Build 10 cathedrals

- Build 10 mills

- House 50 nobles

- Hire 500 soldiers

- House 100 clergy

- House 500 merchants

- House 20,000 serfs

- Own 60,000 hectares of land

- Own 50,000 florins

- Achieve an economic factor 50 (not directly visible)

You don't need to achieve all of these goals in order to win, but each is worth up to 10 points, with partial credit given for partial completion. At the easiest difficulty, you must earn 48 points. At the most difficult, you must earn 72.

After spending some time coming to grips with how things work, I went for the highest difficulty, Grand Master.

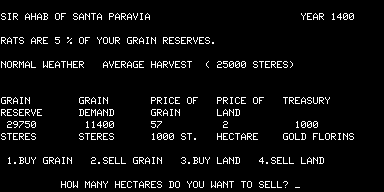

Each turn has three decision-making phases, starting with the harvest.

Here, we already have some improvements from the Hamurabi format. Instead of simply buying or selling land for grain in a one-time, irrevocable decision, you may buy or sell both grain and land for currency. Make a mistake and buy the wrong amount of land? It's okay, you can just sell it back. Unfortunately, there's no good indication here of the amount of land you currently own, so you'll need to keep track of that yourself.

Once

you commit your purchases, you have to decide how much grain to

distribute. The amount must be between 20% and 80% of your reserve.

Here, there's a critically important factor - always distribute at least 130% of the demand. If you haven't got enough grain, buy it. If you haven't got enough money, sell some of your land or accept debt. This encourages people to come to your land - not just serfs, but also nobles, merchants, and clergy, who you absolutely need on the higher difficulties. Furthermore, you get an economy bonus. The number of serfs who come is affected by the amount of extra grain you give them, but the rest don't care - you either meet the 130% threshold or you don't.

Two other factors are important but not quite as much, because unlike in Hamurabi, grain production isn't everything. The amount of "workable" land is equal to your number of serfs times five. To optimize your harvest, you will have enough leftover grain to seed your lands at a rate of one stere per two hectares.

Hidden from this screen are your serfs and hectares. We always begin with 2000 serfs and 10000 hectares, a perfect proportion so that all of the land is workable.

Math time. 130% of the demand is 14820. I will also need 5000 to seed all of my land. If I have 19820 steres, these plans work out. 14820 is less than 80% of that total. I already have more than that, so I sell the difference rather than let the rats eat it.

Prior experience tells me that I can count on collecting 1500 florins in taxes on my first turn. Land isn't cheap right now, but it's inexpensive enough to pay off later, so I'll buy 1533 hectares for 3066 florins and end my turn exactly 1500 in debt. And finally, distribute the 14820 steres to the people.

|

| Paravian babies are born ready to work. |

As I mentioned, whenever immigration occurs, it includes nobles, merchants, and clergy. This is kept hidden from you, for some reason.

The next phase is taxes.

You can play around with the rates and see your projected income before committing. The instructions say that high taxes slow economic growth, but this isn't quite accurate. There are two rules, which come into effect the following turn:

- If the sum values of Customs and Sales taxes add up to under 35%, then 1-4 merchants will immigrate.

- There is a (100% - 5*[INCOME TAX)) chance that 0-1 nobles immigrate, and 1-2 clergy immigrate.

I want nobles and clergy, so I keep income tax at zero. And I've found that customs duties always pay better than sales tax, so I keep customs at 34% and sales tax at zero.

But the real money comes from corruption. And that brings us to justice.

The maximum level is "outrageous," where the judges are bribed, verdicts go to the highest bidder, and you get 700 florins per title you've achieved. SoftSide says this harms the economy, but I haven't seen any proof of this. There are two main downsides - the first is a severe score penalty. And this isn't that big a deal - just set it to "fair" on turns where you think you'll get promoted, and the score penalty will immediately go away. Then you can go back to outrageous justice once you acquire a new title; you can't get demoted by losing points, and you'll enjoy even more lavish kickbacks with your higher title. The second downside is that serfs tend to flee, but with my 130% grain demand strategy the population seems to trend upward regardless, and I don't need a lot of serfs to win as long as they produce enough grain to feed themselves and everyone else.

Before the third phase, we get a view of our fiefdom.

|

| And an anticipation of Civilization's city view |

This is mostly visual fluff, but the icons here are meaningful. The size of the rectangle indicates how much land we own. The squiggles in its upper-right corner are supposed to be a plowman driving a horse, and its position indicates optimal grain harvesting for the amount of land owned - when we have too many serfs to put to work, he'll be above the line, and when we have unused land, he'll be farther below it. Lastly, the castle in the upper left means we are adequately defended.

The final phase is state purchases.

- All buildings improve the economy, and the more expensive the building, the bigger the effect.

- Marketplaces generate 75 florins every turn - hardly amazing as it takes 14 turns to turn a profit and your game isn't guaranteed to last more than 20 - but also attract merchants.

- Mills generate 56-305 florins every turn and improve the economy even more, but each mill owned causes 100 serfs to be unproductive for harvesting grain.

- Palaces attract nobles.

- Cathedrals attract clergy.

- Soldiers are needed as your land grows, or you risk invasion. Each platoon bought converts 20 serfs into soldiers, and will cost 60 florins every turn.

For now, I invest in a single marketplace, and the turn ends.

Here, grain is cheap and land costs more than I want to pay for. So my strategy is to buy as much grain as I can and still have manageable debt, and give it all to encourage serf immigration.

I buy another 2 marketplaces.

For the next few years I continued this pattern, selling extra grain, buying land on credit, and refilling my pockets through Machiavellian justice. By the year 1405, I was pulling in over 3000 florins per turn, owned 10 marketplaces, and my population included 11 nobles, 45 soldiers, 16 clergy, 118 merchants, and 2595 serfs working 13146 hectares of land. It was time to seek a promotion, so I temporarily set my justice level to "fair" and lived the next turn in austerity, buying just a mill when I could have otherwise afforded two.

|

| Yes! |

|

| New taxes under Baron Ahab. That crown won't buy itself. |

With my newfound wealth I bought three mills in 1406 A.D. And this was just the beginning. With each turn, wealth increases - more merchants mean more duties, improved economy means more tax revenue (i.e. more duties), more mills mean more export revenue, and more titles mean more payola. But the cost for more titles goes up as well - at first you can advance through marketplaces at a cost of $1000 per point, but no more than ten count. Eventually cathedrals cost $5000 for the same prestige benefit, though they also bring in clergy and further improve the economy.

By 1409, I became a count, was bringing in 5899 florin per year, and acquired my tenth mill. I started investing in soldiers, which provide no economic benefit other than land protection and require yearly salaries, but at an up-front cost of 500 florin per 20 men, it would only cost me 12,500 florin to get the maximum score bonus and advance another rank.

It only took until 1411 to reach the next rank, Marquis.

Poor harvest meant I had to buy grain at inflated prices to meet demand, let alone the 130% rates I'd always done, but the price of land had doubled, so I simply sold some of my extra, unused land to make the gold difference. I bought 18,028 grain and sold 285 hectares, and the immigration continued as I allocated 31,857 steres of grain despite the shortage.

Taxes and bribes were now bringing in 7432 florin per year, and I could start building a palace to advance my rank further.

|

| Depicted: Castle, partially finished palace, ten marketplaces, ten mills. |

1413 A.D. saw my promotion to Duke, and another poor harvest. No matter, I was bringing in 9180 that year, and bought five more palace installments. The next year I bought the last one, and in 1415 A.D. was promoted to Grand Duke, and brought in 11,176, which I began investing in expensive cathedrals.

At this point I stopped buying land except for when it became unusually cheap. The money would be better spent on a cathedral.

|

| Complete palace and in-progress cathedral. |

In 1418, I got promoted to Prince, which could have brought in 13821 florins, but I was pretty sure the end was near, kept justice fair, and finished the cathedral, paid for on borrowed coin. This, combined with my population, was enough to get me crowned king.

GAB rating: Above Average.

Santa Paravia was recommended to me almost two years ago, and I'm glad I played. It isn't going to blow any minds today, it's not especially

convincing as a simulation or as a historically accurate setting, and

success at higher levels depends entirely on understanding its invisible

rules, but planning my city, managing harvests, and seeing my numbers

go up as I made the right decisions was a fun little spreadsheet

exercise. It's not hard to see how games like Civilization and SimCity

might have been inspired by its gameplay family, if not by this exact

title.

Coming up next is an all-time classic.

Thank you for "solving" this game - it is the kind of game I really don't want to play, but I really want to know more from the "historical" point of view, including on design.

ReplyDeleteInteresting how the very early games had pretty "high culture" settings : ancient Sumer, Renaissance Italy, ...

You may want to take a look at "Civil War" (1968), which is an Hammurabi-like game about the US Civil War. I can't gather the will to play it, but it will be interesting to have your analysis of how your "logistics" decision impact the result of the battles.

I did check it out a little bit. There's a BASIC listing from Creative Computing here:

Deletehttps://www.atariarchives.org/bcc1/showpage.php?page=256

TBH it isn't all that Hamurabi-like, because there's no economy. You get money and decide how much to allocate on food, salaries, and ammo. And then you pick a strategy.

I got as far as figuring out the optimal food and salary distribution. These affect morale, determined in this line:

230 LET O=((2*F^2+S^2)/F1^2+1)

In other words:

Morale = (2*Food$^2 + Salary$^2)/(Food Demand)^2 + 1

Food Demand is $5/6 per man, determined in an earlier line.

Basically, just allocate $1.77 per man on food and give them no salaries to ensure a morale of over 10, which is the highest meaningful value.

I did not care to decipher the effects of ammo budget and strategy. The immediate effect is on your own casualties, calculated by these four lines of hell:

410 LET C5=(2*C1/5)*(1+1/(2*(ABS(INT(4*RND(1)+1)-Y)+1)))

412 LET C5=INT(C5*(1+1/O)*(1.28+F1/(B+1))+0.5)

414 IF C5+100/O<M1*(1+(P1-T1)/(M3+1)) THEN 424

416 LET C5=INT(13*M1/20*(1+(P1-T1)/(M3+1)))

C5 is your casualties. C1 is historical casualties for the battle. Y is your strategy, and B is your ammo budget. M1 is your men. P1 is accumulative casualties, and T1 is accumulative historical casualties. M3 is the total number of battles fought so far.

I won Bull Run with 2058 casualties, but when the next battle, Shiloh, informed me that I had -3999996 men, I stopped playing. I don't feel like trying to figure out where the error here is.

Woot ! Thanks for investigating. I assume it was Hammurabi-like, and actually hope it was. I guess I will have to cover it - and your calculation will be invaluable.

ReplyDeleteYou won Bull Run with 2K+ casulaties... but for which side ?

In this version you always control the Confederate Army.

Delete"The instructions say that high taxes slow economic growth, but this isn't quite accurate."

ReplyDeleteLOL! The long reach is Reganomics.

One place where Reaganomics does factor is that the tax system follows a Laffer curve. During my trial runs I'd obsessively fine-tune the tax rates to maximize projected revenue. Corruption is much better in the end, though.

DeleteOh man... Reading your playthrough, I've now suddenly realized where one of my favorite C64 games from back in the day got its inspiration from: Ariolasoft's 1984 game "Kaiser". https://www.mobygames.com/game/71050/kaiser/

ReplyDeleteIn it, you also need to buy land and grains, and gather influence and money to advance in rank until eventually you're declared emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

Aside from a nicer graphical representation, as far as I can tell the only major difference lies in random events like bad weather leading to spoiling harvests, and an additional quasi-strategy war gaming element where you can hire mercenaries and use them to attack your opponents merchant routes, robbing some of their annual revenue in the process (which you mostly can do without in a Single-Player game but gives multiplayer rounds a bit more of an competitive edge). It was never released outside of german-speaking countries, but you could say it earned something of a "localized whale status" around here - it was one of the best selling games in Germany that year. I've spent countless childhood hours with that game

(as an addendum, Kaiser is the linchpin game that led led to the German prevalence on mercantile strategy games - you could say there's a direct line from this game to the later "Patrician" series and the still ongoing "Anno..." Series of games.)

DeleteOh, neat! Would you say Ports of Call is part of that line, or of comparable importance?

DeleteMaybe as some form of cross-pollination... Hanse was directly inspired by Kaiser, The Patrician was a follow-up to Hanse, Port Royale was developed by some of the staff of The Patrician, etc ...

DeleteI *think* Ports of Call was inspired directly by Hanse, and added a better presentation (especially in the graphics department) and a few twists (like that arcade style harbor sequence). But AFAIK PoC was kind of a dead end... At least its developers never worked on any other game in that vein. Of course it could be that some later developers took inspiration from PoC as well, but I have no concise info on that. I could try looking into the matter though.

That being said, Ports of Call has some semi-lengendary status in German Amiga Circles (I've seen some german Top 20 or Top 30 Amiga games lists that include that game), and I wouldn't be surprised if some later developers were kind of inspired by that game later on. In terms or direct lineage though, it appears to be more of an outlier.

DeleteOh yeah, and for completion's sake: the first game in the Anno series, Anno 1602, took direct inspiration from The Patrician, The Real-time strategy-and-production-routes aspect of The Settlers and a dash of the works of Sid Meier (Pirates and Civilization in particular).

DeleteI also checked again and saw that Kaiser *did*, in fact, see an UK release. From what I can tell, the game was originally released in Germany on tape in 1984, saw a Disk-Release in 86, and that disk release was also translated into English and released in the UK that same year.

(Sorry for the many single posts, would've edited an earlier reply if Blogspot would allow that).

Well, I had to look it up myself now because I couldn't shake the thought. 😅 I can now confirm that Hanse had an influence on the creation of "Ports of Call". I found two sources where Rolf Dieter Klein himself stated that he was aware of the other German economic/strategy games at the time and points out having played Hanse in particular before embarking on the development of Ports of Call. One source is a German retro gaming podcast (no Transkript unfortunately), but he also told that story to a retro gaming website (a Norwegian one of all places) : https://spillhistorie-no.translate.goog/2024/06/12/historien-bak-legendariske-ports-of-call/?_x_tr_sl=no&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=de&_x_tr_pto=wapp

ReplyDeleteAnd just in case you're interested, the lead platform for Hanse was the Amstrad CPC.

Yep, that does interest me! Also, for some reason, I had been under the impression that there was a connection between Merchant Prince and The Patrician, but as far as I can tell now there isn't one.

DeleteI don't know if I'll wind up diving into the world of German trading sims, but if I do, everything you've explained will be invaluable - I'd never heard of Kaiser or Hanse, but obviously both are critical ancestors. Ports of Call doesn't quite make mandatory whale status - it's big enough that I may consider it as a discretionary one, but if it's an evolutionary dead end then I don't know. My earliest definitely-a-whale German strategy game would be The Settlers, though I'm not sure if it fits in with the Kaiser->Hanse->Patrician lineage (Mad TV before it is a discretionary candidate but the connections seem even flimsier).

Well, you've still got quite a way to go for "The Settlers". ;) For that one, important predecessors would be the games "Historyline 1914-1918" and "BattleIsle" by Blue Byte, which were turned-based strategy games. Combine that with the Mercantile aspect of games like Hanse and the "Real-time cutesy figures fighting another" from Populous - and voilà, you got "The Settlers".

DeleteOh man, I loved Mad TV. Don't know too much about its lineage though. It's got its roots in the German economic sims as well - Rainbow Arts developer Ralph Stock cited Hammurabi and Kaiser as early favorites, he himself cut his teeth on Adventure games like "Der Stein der Weisen" and "East vs. West: Berlin 1948" before he made Mad TV. But I actually know someone who used to work at publisher Rainbow Arts, so I could try asking around a bit

Okay, I did ask around (and also listened to another German podcast). I was basically right regarding Mad TV. Ralph Stock had already developed a few adventure games and wanted to do a trading sim / business sim next, which were popular at the time, albeit one that was, in his own words, "actually fun, and not just looking at spreadsheets the entire time". In the mid- to late 80s, the first Independent TV stations were popping up in Germany, which at the time felt fresh and exciting, so he decided to use that as inspiration (there were already a few TV station sims out on the British market, but he says he wasn't aware of them).

DeleteMad TV was a huge hit around here and in its day one of the biggest German games. The game is also significant in other areas: Rainbow Arts were, at the time, the first German developer who hired people specifically to create video game assets. Up to that point, must were just publishers who distributed games sent to them by "bedroom coders", maybe helped give some games more shine and polish by hooking up some hopeful bedroom coders with some sound or graphics guys they knew. But Rainbow Arts were the first one to specifically hire an in-house musician for games (the legendary Chris Hülsbeck, though I don't think he worked on Mad TV), and who specifically hired people to act as Game Designers and producers. Ralph Stock was one of the first of them, and Mad TV was the first big hit published under that new (well, relatively new, for the German market) business model.