I wasn't originally planning on doing 1980's Olympic Decathlon. I knew it existed, if only because it was one of Microsoft's earliest gaming products, but it didn't occur to me that it had any historical significance or that it had influenced anything. But I've played Konami's Track & Field, a game thematically similar to Activision's Decathlon from a few months earlier, and the similarities run deep. They're not identical by any means, but both are minigame collections controlled mainly by furiously bashing the controls to build speed, and occasionally pressing a single button with pinpoint timing to jump or throw. It seemed like one had to influence the other, but the dates don't work - The Activision Decathlon appears to have been released in August 1983, and Track & Field in October. Could an arcade game, with its bespoke PCBs and cabinet design and manufacturing, really have been produced in two to three months? Plus, how likely is it that The Activision Decathlon was known to anyone in Konami, given the system's relative obscurity in Japan?

Then it occurred to me to try Microsoft's Olympic Decathlon, which had been originally released for the TRS-80 in 1980, ported to Apple II in 1981, and ported to the IBM PC in 1982. So I did, and can conclude almost for certain that it influenced both Activision and Konami in similar ways, and also in different ways.

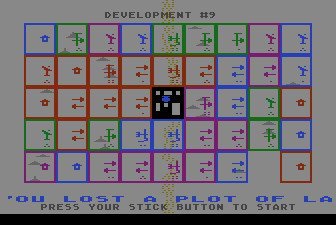

Game 259: Olympic Decathlon

|

| The IBM and Apple versions' titles are preceded by the Microsoft logo, but the TRS-80 original is not. |

I'll be taking a look at the ten events here and comparing their

interpretation and execution to the later Activision and Konami games. I

will also discuss the Apple II version where it differs or expands, as I

believe that this is the version which principally influenced the

Konami game. Speaking of which, the Apple II and IBM versions both play

Bugler's Dream, as does Activision Decathlon.

|

| TRS-80 intro |

|

| Apple II intro |

You can practice individual events or compete in the full decathlon, just like in Activision Decathlon.

The 100 meter dash has you tapping the "1" and "2" keys alternately to simulate your left and right footsteps. Activision Decathlon takes a similar approach except that you waggle the joystick left and right instead - something far more strenuous than tapping keys, though to be fair I have no idea how different it feels on an authentic TRS-80 keyboard. Uniquely, Olympic Decathlon has you approach the start manually, which is kind of a clever ingame tutorial, straightforward as this action might seem.

When playing with more than one contestant, two players dash at once, and the second player uses the left and right arrow keys and runs in the second lane. The Atari 2600 version of Activision Decathlon only supported one sprinter at a time, but later ports allowed two, as did Track & Field.

One crucial similarity between Activision Decathlon and Track & Field not seen here is the side-scrolling perspective.

Next, there's the long jump.

Here we can already see some big gameplay differences in this family. Olympic Decathlon gives your sprinting arm a rest - you simply type into the program how fast you'd like to run, knowing that the faster you approach the line, the more challenging it will be to time your jump close to it. Jumping is a two-keystroke action - down plants your feet and starts an animation, enter launches yourself, and the delay between determines your jumping angle.

|

| The Apple II version's pretty similar, just more colorful. |

Event 3 is the shot put.

This involves some QWOP-like shenanigans with separate controls for your triceps and shoulder muscles. It's confusing, uncanny, awkward, and kind of awesome. And you don't see anything like it in Activision Decathlon where it's fundamentally the same as the long jump.

The Apple II version requires paddles, and if you don't have them, you're stuck here.

I haven't quite figured out the timing involved, but paddles feel better here than keyboard controls. Also, unlike the original, we get a zoomed-out view of the field once the shot is thrown.

The high jump is similar to the long jump, but with different angle

requirements, and also no option to set your own speed. Also that

instead of recording your best of three trials, you instead must clear a

series of bars with progressively incrementing heights, just like in

the real-world event.

The 400m run is just like the 100m dash, but four times as long, and

you go all the way around the track. This one made my arm start to hurt,

but it's nothing like the brutality of Activision's version.

Now this is interesting. If I'm not mistaken, the 110m hurdles event is the earliest example of sidescrolling I've ever seen, predating Defender by a year!

The controls are kind of interesting too, but not fully explained in the game. You run by alternating presses of 1 and 2, but jump by pressing and holding both at once. Unfortunately, there seems to be a delay that can't be easily predicted. Activision Decathlon and Track & Field both simplify this to a single button press for jumping.

The Apple II version uses the buttons on the paddle controller - and rapidly tapping them alternately on my Atari paddles is no easy task! Jumping seems more responsive, though, and this time the hurdles actually topple when you fail to clear them.

The discus is all about timing. You set your turning speed manually, and then tap a button at the right time to toss - the higher your speed, the further you can potentially throw it, but also the more difficult timing becomes.

The Apple II version is pretty much the same, except it adds a zoomed-out field view. Which we'll see again in Konami's game.

Activision's interpretation bears little similarity here - you just run

up to the fault line and press the button before crossing it, just like

the other field events. But Track & Field lifts this almost

wholesale for its hammer throw event.

Look at all those controls! Is this a vaulting pole or a Cessna?

The pole vault is probably the most complicated event in the game. First you have to manually set your grip height and your runup length. I don't really know why you'd want your runup to be anything less than the maximum length, but a shorter grip height makes building up momentum easier.

You run up to the box by alternating left and right arrow keys. Then you press down to plant the pole into the box, but you've got to do it a bit early. Just as importantly, do not stop tapping left and right until the pole is lowered all the way into the box! Once it's planted, up begins the handstand, and Clear (mapped to Home by default in MAME) releases.

Activision's version is quite a bit simpler - you just have to run, mount, and dismount.

To throw the Javelin, you run toward the fault line with left and right, press up to begin your throw, and press enter to throw. Timing determines the angle, and if timed well, it will be launched at the optimal angle close to the fault line, but the angle is far more important (as long as you don't go over the line).

The Apple II version of this event, like the discus event, adds a zoomed-out field view.

Activision once again simplifies this - you just have to hit the button close to the fault line like in all of the other field events. Konami's version is closer in execution.

The final event is the 1500m run and it's weird. They could have

busted your keyboard with a marathon of tapping 1+2, but instead you use

the WASZ keys to just move around the track, and try to stay on it.

It's bizarre and doesn't feel anything like an endurance race, but given

the pain of Activision's version I'm kind of glad. The straightaways

involve no skill - you just hold the right directional button, and the

curves are about transitioning to diagonals with the right timing.

What's kind of interesting to me here is that you have to hold

the keyboard buttons to move in that direction. That might not sound

special, but the Apple II and early IBM PC models didn't support this,

because apart from modifying keys like shift and rept, their keyboards

only recognize when you press a key, not when you hold it

continuously. So clearly the TRS-80 keyboards were a bit more forward

thinking in their design, in some aspects. The Apple II version makes

you tap WASZ to "steer" rather than move in an absolute direction.

Even more interestingly, this event allows two players to race at

once, and assigns the second player the PL;. keys. If both players

wanted to move northwest at the same time, player one would need to old W

and A, while player two would have to hold P and L. This does not work

on my modern, USB keyboard! And it probably doesn't work on yours

either. For technical reasons I won't get into, most USB keyboards choke

on certain combinations of simultaneously pressed keys. So it appears

that the TRS-80 supported n-key rollover, which is expensive to

implement. Or maybe this event is broken on a real machine too.

My best decathlon scored over 7,000 points, far better than my Atari attempt.

GAB rating: Average. This isn't really my kind of game, but I like it better than The Activision Decathlon. All of the events feel and play distinct from one another, and don't leave me feeling like I'm giving myself arthritis.

With this predecessor scrutinized, how does Konami's Track & Field compare?

Game 260: Track & Field

I actually saw a Track &

Field machine in public recently, and it was a sad sight to behold,

with cracked, barely working buttons, and a scuffed, faded control panel overlay. To play it for DDG, I used my

arcade control panel with concave Happ microswitch pushbuttons.

With

the assumption that both Activision Decathlon and Track & Field are

adaptations of Olympic Decathlon, there are still a couple of

similarities in how both games reinterpret the events for their

respective platforms.

- Both games use a side-scrolling perspective extensively.

- Both games emphasize button-mashing to simulate running for most of the events.

But there are more general differences than similarities.

- Track & Field obviously has a much more advanced presentation, with parallax scrolling, realistically-proportion multicolor sprites, and speech synthesis that produces intelligible barks (e.g. "the distance is seventeen point six one meters").

- Activision Decathlon simulates running by waggling a joystick back and forth. Track & Field has two "run" buttons and a third "jump" button, but doesn't seem to care if the "run" buttons are alternated. In fact, I got better performance when I mashed just one of them.

- The Activision Decathlon adapts all ten events. Track & Field has only six, including a hammer throw instead of a discus.

- Track & Field has a much more punishing difficulty, where each event has a qualifying score, and failing to reach it will end your game. There is also no option to practice specific events.

- The Activision Decathlon has Olympic decathlon-style scoring. Track & Field uses an invented aggregate score system, but also records the top three scores for each individual event.

- The Activision Decathlon uses Bugler's Dream as its theme. Track & Field uses Chariots of Fire.

The 100m dash is as basic as it gets - just bash "run" like mad. As I mentioned, there are two run buttons, but I performed better when I hit only one of them.

This version always has two runners, and if you are playing solo, an AI opponent will race in the second lane. It doesn't matter who wins, though. You don't need to beat him, you just need to beat the qualifying time.

The

long jump has you bash "run" to get to the fault line and jump as close

to it as possible, much like The Activision Decathlon. But unlike that

game, you also have to optimize your angle, as in Olympic Decathlon,

which is done here by holding the jump button and releasing when the

onscreen angle indicator is as close to 45° as possible, which, defying physics, affects your trajectory mid-jump.

The javelin event is basically the same thing as the long jump. It's a bit closer to the Olympic Decathlon event as in that one you still have to do the work of running up to the line, though here you want to begin your throw as close to the line as possible, and in the original you need to give yourself a fair bit of clearance first. Olympic Decathlon is more realistic feeling and more strategic as a result.

110m hurdles is simplified and winds up being just like Activision Decathlon. Run and tap jump at the right times to clear the hurdles.

Hammer Throw is almost exactly the same as Olympic Decathlon's discus event, down to the overhead perspective and zoomed-out view. The main difference is you don't set your speed - you just press the throw button to start spinning, and your speed automatically ramps up exponentially. No button mashing is required, for once.

I

couldn't beat this one, but it had more to do with the difficulty in

reaching this stage than in beating it. I only reached it once, and

eventually got fed up with trying to get to it again. Control panels are

expensive, and so is RSI surgery.

GAB rating: Below Average.

It's better than The Activision Decathlon, but not as good as Olympic

Decathlon despite the improved presentation. The games in the TRS-80

original just have more variety, more depth and authenticity, and actually let you see all of the events without needing to meet some pretty stringent qualifiers.