Flying over the north beach, I reached the mountains, and knew I had to be near the castle. Encountering a rickety footbridge across a chasm, the game warned me it could not support much weight. I wasn’t sure what to do, but figured that rather than tediously drop everything one item at a time, I could just use the magic word LUCY to instantly lose everything, and then at least explore the other side for a little while.

This turned out to be the right thing to do. I found all of my stuff in a cave on other side of the bridge.

Recollecting all this stuff took FOREVER. The whole screen has to slowly redraw itself every time you take something!

This mountain region had two ephemeral events that required immediate action, or else the game would become unwinnable. First, one screen had a rainbow, which would vanish the moment I stepped away.

Here, you have to type “GO RAINBOW,” which takes you to an otherwise inaccessible room with a gold coin. If you don’t do this immediately, the sun comes out and the rainbow vanishes.

The second event is the appearance of a peddler, hawking some goods. When you leave this screen, he and his goods will be gone forever, whether you bought one or not.

Only one of these items will be useful, and you’ve only got one coin, so you just have to keep a save file right here until you know which item you need. This would have so much potential for cruelty, except for the fact that the the next obstacle, where you will need one of these items to proceed, is dead ahead.

Harlin's castle, two rooms north, is the next obstacle, and you blow the peddler’s horn to lower the drawbridge. Why would announcing my presence to the enemy cause them to just let me in like that? I'd expect them to raise their defenses, not lower them! Or possibly get zapped back to the desert by an alerted wizard, or worse. Who knows.

There’s a rather large maze in the castle, but mercifully, every direction in it is clearly indicated, and it mostly obeys Euclidean geometry. Other rooms in the castle seemed to attract the attention of the wizard, who would magically teleport me away, either back to a previous room, or to a courtyard with an angry boar I could easily kill by feeding it my apple, or to a prison cell with no apparent way out.

The maze leads to the dungeon and a few rooms beyond, including a tower with a bird flying around.

I had to resort to a walkthrough to progress. That bird is the evil wizard! There's no way to deduce this except for after the fact; once you kill the bird, the magic attacks stop happening. By rubbing a sapphire ring found earlier in the mountains, I turned into a cat and ate him. I'm not sure if Harlin is actually a bird or if he just turned himself into one for some reason, but either way, this puzzle stinks.

Free to explore the castle, Princess Priscilla was only one room away, secretly transformed into a frog.

Kissing the frog, of course, freed her.

Two rooms over was a closet with some shoes that had another magic word printed on them.

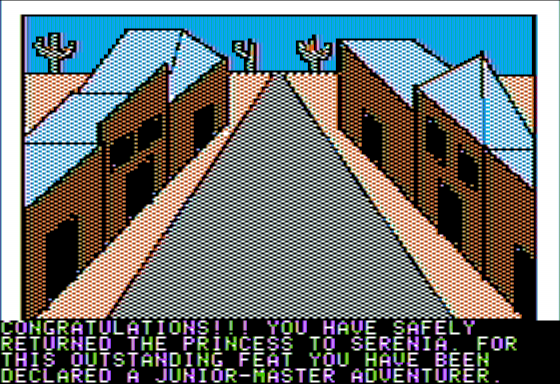

WHOOSH took me and Priscilla back to Serenia, ending the game.

|

| Thanks, but wasn't I supposed to get half the kingdom? |

So ends another early Sierra game, and it’s an improvement over Mystery House in every way, and also the most King's Quest-like of the Apple II Sierra games. It's not surprising, then, that Sierra's quintessential series would eventually return to Serenia, establishing it as part of the setting canon. The princess-saving quest format which anticipates so many King’s Quests may seem trite nowadays, but considering that most of the adventure games I’ve looked at so far were variations of Adventure’s treasure hunt, it’s almost a novelty to see this template used instead, and it fits the limited technology of the Williams’ basic parser and world modeling better than the underdeveloped Mystery House could. The world design is linear compared to other adventures, with a clear thematic world order of Desert->Forest->Sea->Jungle->Mountains->Castle, but this promotes the feel of adventure, as every leg of your journey north brings you tangibly closer to your goal. When you finally arrive at the castle, there’s both a sense of accomplishment at how far you’ve come, and a sense of dread at what lies ahead.

There are still plenty of stumbling blocks, and the most damning of them was that there wasn’t a single puzzle in the game that made me feel clever for having solved it. The world model is about on par with Scott Adams’ adventures of the day, and is poorly suited to complex Zork-like puzzles. But the simple puzzles by Adams occasionally felt satisfying, thanks to some signposting that gently nudged me toward obscure solutions for unsolved challenges. Wizard and the Princess never managed this, and every puzzle that I solved either felt trivial or felt as if I had stumbled upon the solution by accident. Whenever I did need to look up a solution, with the sole exception of HOCUS, I just felt annoyed, as if there was no way anyone could reasonably intuit that solution on their own.

The desert area, with the search for the one rock that won’t kill you is the worst part of the game. The parser is improved but still bad, still bad, and the graphics, though possibly the best in the world available to consumers in 1980, are amateurish. Prose is a bit improved from Mystery House, and the game occasionally gives responses to actions you aren’t required to do – a luxury the Scott Adams adventures never had - but we’ve got Zork to compare it to.

We also see most of the adventure game sins of the type that Sierra would become infamous for in the 80’s and early 90’s, though this doesn’t bother me that much per se. It eventually became an unwritten rule that an adventure game must be reasonably beatable with a single save game file. To ensure this, there are a number of things an adventure game must not do; it must not kill you without fair warning, it must not have puzzles that require knowledge of events that have yet to happen, it must not allow you to waste items that you will need later on, and it must not have missable items or events without allowing you to backtrack to them.

Wizard and the Princess breaks all of these rules, ensuring that you can’t reasonably beat it on a single save file, but again, this doesn’t bother me that much, because I don’t see why an adventure game must follow that rule, so long as it is upfront about its design and the player’s need to keep multiple saves. I can certainly see why a designer would prefer this kind of design. LucasArts practically codified it and got superlative mileage out of it, but I feel there’s room for more than one kind of design philosophy. Infocom’s most complex and satisfying puzzles wouldn’t be possible if every move was guaranteed to move you closer to the solution without fear that it might have locked you out of the solution instead. Wizard and the Princess hasn’t got any complex or satisfying puzzles, but the final area does instill a sense of unease, which it couldn’t have if you went in knowing a designer’s safety net was always underneath you.

My Trizbort map:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Commenting with signin or name/URL is encouraged but not required. If the spam filter deletes your legitimate comment, apologies - it does that sometimes.